The Beginnings of Silk Production

The origins of silk production in ancient China are steeped in legend and antiquity. It is believed that silk was first discovered around 2700 BCE during the reign of Emperor Huangdi. According to Chinese mythology, Empress Leizu accidentally discovered the process of unraveling silk from silkworm cocoons when a cocoon fell into her tea. Regardless of the legend’s authenticity, silk quickly caught the attention of Chinese society owing to its remarkable qualities.

Silk, from its inception, became more than just a luxurious textile; it heralded a new era in ancient China’s cultural and economic framework. As people began to understand the intricacies of silk cultivation and weaving, this initiated a cycle of innovation that saw more sophisticated techniques develop over time. The ancient Chinese soon found themselves at the center of a trade empire that flourished wealth through silken threads woven from the cocoons of the Bombyx mori moth.

Silk as a Catalyst for Economic Growth

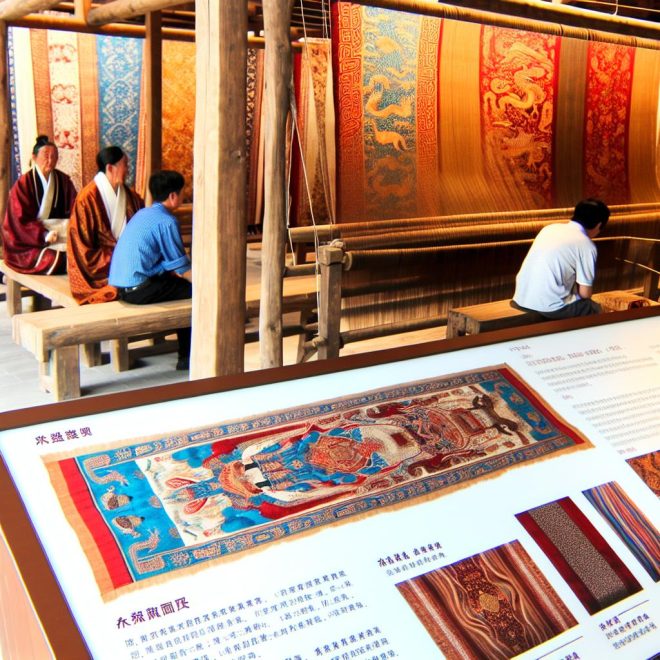

Silk production became an integral part of the ancient Chinese economy. The initial stages of sericulture, or silk farming, were labor-intensive but gradually became refined over the centuries. Eventually, the processes involved in sericulture became more sophisticated, leading to improved efficiencies that allowed silk production to scale effectively. This evolution from a cottage industry to a more organized form of production played a pivotal role in the early economic systems.

The growing demand for silk within and beyond China’s borders led to the development of a burgeoning industry that employed large numbers of people in both rural and urban areas. Silk’s unparalleled strength and luster made it the fabric of choice, and with increased production capabilities, its reach extended even further. The silk workers, initially attached to small familial units, found themselves part of a larger socio-economic structure. Villages turned into bustling hubs, akin to early forms of industrial towns.

The high value of silk facilitated the collection of taxes in the form of silk fabric. The government, in turn, stocked these as part of its treasury reserves. This added a unique dimension to China’s economic stability, as silk became a form of currency that could be traded and stored with relative ease. Much like gold in later societies, silk’s status transcended its form; it became a principal component of economic transactions.

The Role of Silk in Trade Networks

One of the most significant contributions of silk to the ancient Chinese economy was its central role in establishing the Silk Road. This vast network of trade routes linked China to the rest of Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, and facilitated the exchange of goods, culture, and even ideas. The term “Silk Road” itself underscores the importance of silk as a primary commodity traded along these routes.

Merchants carried silk as far as the Roman Empire, where it was highly prized. This long-distance trade not only enriched Chinese traders but also helped integrate various regions into a global economy. The allure of silk in far-off lands introduced exotic exchanges, where spices, incense, and precious metals were brought to China, further increasing its cultural and economic tapestry. As silk flowed outward, cultural influences disseminated into China, creating a mosaic of shared experiences.

Besides material exchange, ideas traversed these routes as well. Philosophical, religious, and technological knowledge spread along with silk, impacting both distant lands and China itself. While the material prosperity associated with silk trade was unmistakable, its capacity to connect diverse societies stands out as its perhaps most enduring legacy.

Silk and Social Implications

The economic impact of silk was not solely confined to trade and commerce. As the industry evolved, it also influenced social structures. Silk production became a vital cottage industry for many rural families, providing a source of income and economic resilience in agricultural areas. As demand surged, entire communities structured their livelihoods around the silk cultivation process.

Provincial areas saw increased agricultural activities dedicated to the cultivation of mulberry trees, crucial for the sustenance of silkworms. Agricultural diversification started to pave the way for more permanent and stable communities. The establishment of silk weaving workshops further diversified economic activities, influencing urbanization patterns as families migrated closer to these centers for employment. Thus, cities like Suzhou and Hangzhou became synonymous with silk production and trade.

Moreover, silk emerged as a social marker in ancient times. Certain styles and qualities were exclusive to the ruling classes, while more accessible varieties were available to commoners. This created a complex social hierarchy rooted in the visual opulence that silk afforded. As a societal cloth, silk threads told stories of interconnected lives, bridging class divides and establishing a shared cultural asset.

Conclusion

Silk played a multifaceted role in the economy of ancient China. Beyond its aesthetic and practical value, silk became a linchpin for trade, a medium for tax collection, and a crucial element in social and economic development. The interregional connections facilitated through silk trade brought prosperity and prestige to China, establishing it as a cornerstone in global commerce.

Moreover, as new technologies and innovation have evolved, silk remains a testament to China’s enduring cultural heritage. The historical perspective offered by silk allows modern society to appreciate how a single commodity can shape economic narratives and forge connections between diverse cultures and regions, laying the groundwork for a world system interconnected far beyond the silk threads of its origin.